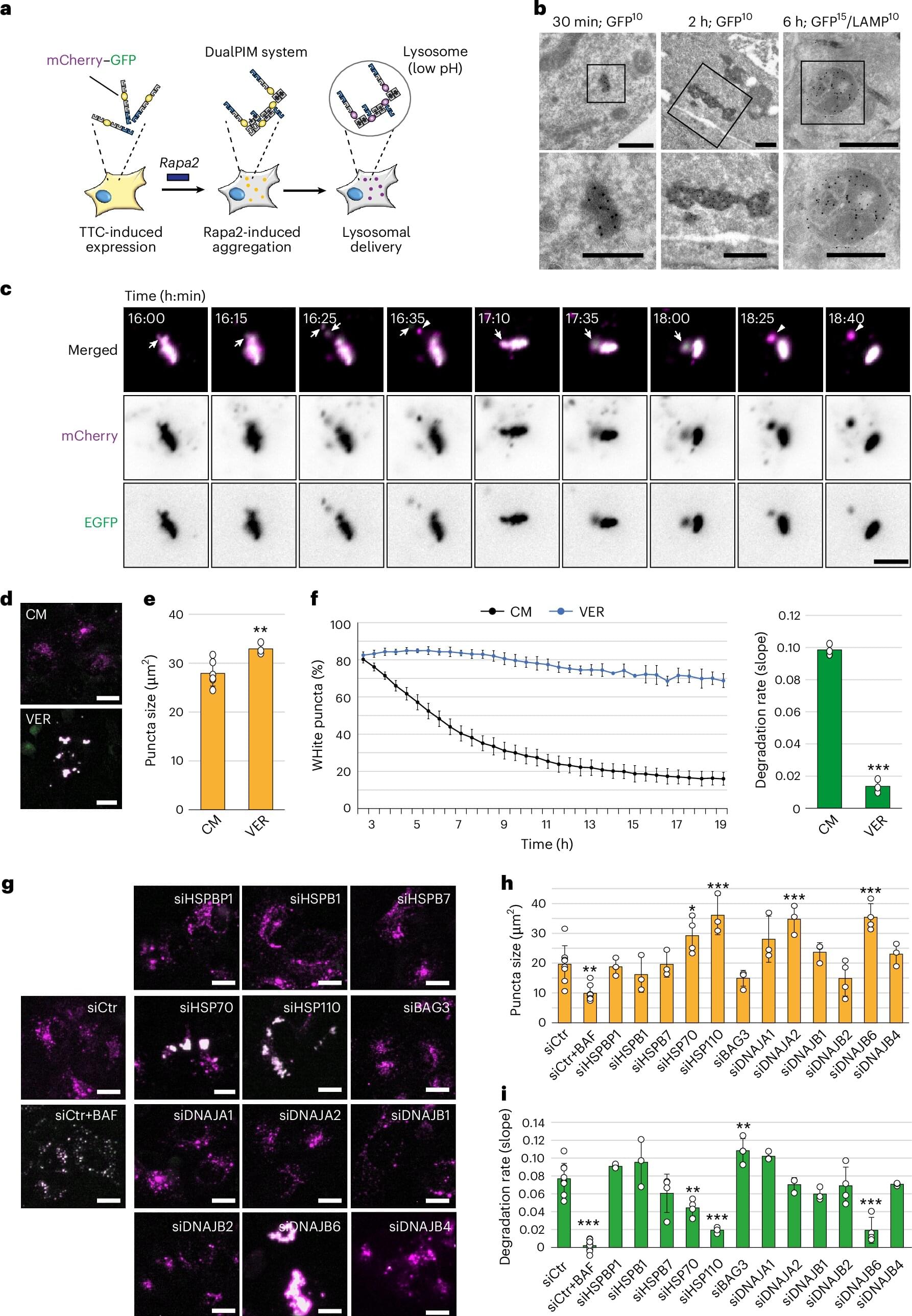

A new study from Aarhus University shows that our cells’ ability to clean out old protein clumps, known as aggregates, also includes a—up till now unknown—partnership with an engine that breaks down bigger pieces into smaller before “taking it to the trash.” An important find for future treatments of diseases like Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, ALS and Huntington’s, which are all characterized by the accumulation of protein in the brain.

Imagine you’re about to eat a big pizza. In order to not choke on it, you cut it up into slices and eat it bite by bite. And while you’re chomping down on your slices, cells inside your body are busy slicing the built-up protein clumps into pieces that are more manageable for the body’s trash system—otherwise it would clog up and malfunction.

Researchers from the department of Biomedicine at Aarhus University have just released a new study, which for the first time documents exactly how those clumps of unwanted protein get reduced to smaller pieces before being disposed of by the cells’ garbage disposal system—called autophagy. The work is published in the journal Nature Cell Biology.